We rarely do as much good as we would like. Our ambitions to leave a legacy of good works can end up indefinitely postponed or dissipated into dead end, do-nothing projects.

I want to live an abundantly pro-social life in service to others. I have mostly failed. This is not advice from someone who is successful. This is an analysis of my failures in the hope that it will help others. The accusatory “you” that I sometimes use is directed at myself.

Doing good is harder and easier than most people realize. It requires thought, care, and attention - but abundant opportunities are passed over for not flattering our egotism and preconceptions.

Why Opposition to Evil is Not Enough

We want more than to just be good adherents to the “silver rule” - “do no harm.” This rule is more robust than the golden rule, and is essential to any functional morality.

But it runs into the “dead grandfather” problem: we can abstain from harm better when we are dead. For life to have meaning there must be good that we can pursue and not just harm to be avoided. There must be a morality of right-doing as well as wrongdoing.

Trying to make the silver rule positive sum can lead to the error of pure opposition.

Opposition is clean. We might conclude that after we have minimized our own causation of harm we can create a surplus of goodness in the world by reducing other sources of harm. Making others refrain from evil allows you to accomplish more good than you would by not existing. You can balance the books by subtracting from others.

This can work. The world needs its cops and prosecutors. But without a conception of the good that is being defended, opposition to evil can easily become unwholesome.

It can take a cowardly, self serving and low effort path, allowing us to cloak our most base instincts in righteousness. Here is a dismally common pattern that explains much of online discourse and politics:

Pick a fight you could lose (with someone stronger), and you might face grievous consequences.

Pick a fight you know you can win (with someone weaker), and it is obvious you are a bully and a coward.

Solution: wait for someone weaker to show moral failure and attack them safely under the cloak of righteousness.

The low effort, low payoff, version of this is to be a member of an online dogpile. A more active way might be to try and be someone in the vanguard of the baying mob.

But even if you avoid this trap, there is a more fundamental, philosophical problem. Evil is interwoven into the fabric of life itself, and eventually all creation starts to appear as an error to be corrected.

At this point, you would rather encounter evil that flatters your egotism than be surprised by beauty and goodness that might undermine your sense of mission. Taken to its logical conclusion, you are a cosmic prosecutor, a condemnor of existence itself.

“Suppose one reads a story of filthy atrocities in the paper. Then suppose that something turns up suggesting that the story might not be quite true, or not quite so bad as it was made out. Is one's first feeling, 'Thank God, even they aren't quite so bad as that,' or is it a feeling of disappointment, and even a determination to cling to the first story for the sheer pleasure of thinking your enemies are as bad as possible? If it is the second then it is, I am afraid, the first step in a process which, if followed to the end, will make us into devils. You see, one is beginning to wish that black was a little blacker. If we give that wish its head, later on we shall wish to see grey as black, and then to see white itself as black. Finally we shall insist on seeing everything -- God and our friends and ourselves included -- as bad, and not be able to stop doing it: we shall be fixed for ever in a universe of pure hatred.”

- C.S. Lewis

Egotism

You want to think of yourself and be seen by others as a person who does good more than you want to do good. Many opportunities to do good have appeared and you have passed them up because they did not flatter your preconceptions.

I went to law school at the end of a disillusionment with left-wing activism (though I did not realize this at the time). It had become obvious to me that my adventuring life as a nomadic anarchist agitator served no one but myself.

But I did not kill the underlying self importance - my desire to be recognized as special and worthy - and so I fumbled many opportunities to do good.

The only real clinical program at my school was a criminal law one - and I did it in first year. The stakes were very low - consisting of people who did not qualify for legal aid because they weren’t facing jail time or deportation.

I liked it. I had an opportunity to help a couple people. I could have followed that clinical program to its course and stuck with it through my whole law degree. I didn’t, even though it was interesting, and I would have been good at it - because a career in criminal defense law seemed icky to me, the people I would have helped too undeserving. I turned away from a role where I might have done good because it did not match up with my own conceits.

Low Effort

We want to do good but we have busy lives. We may be tired or struggling ourselves.

This leads to a marketplace of low effort gestures that we can pat ourselves on the back for and not interrogate too closely.

Here is one of my worst failures: years ago, when I was an undergrad in Montreal, I passed a young man begging on the street. He had a sign saying he was saving for a Greyhound ticket to get to Halifax because his mother was dying. I stopped and asked him if it was true. He looked up at me with red, puffy eyes and told me it was. I believed him.

I think I threw down a bill and mumbled some words of condolence. I gave him more money than I would normally give to a panhandler.

But even on my student budget I could have bought him a ticket, though I might have had to tighten my belt a bit. I might have made a difference in that young man’s life, with only minor inconvenience to myself. I hope he was able to see his mother while she was still alive. If not, there is a tear in the moral fabric of the world that I might have prevented.

Becoming a Skilled and Useful Person

There is an entire industry - likely in decline now - called “voluntourism.” There was a time when volunteering in the third world was considered a very noble thing to do.

The demand for volunteer opportunities exceeds the number of genuinely useful roles. Most voluntourism isn’t very useful to anyone. There are people already in those countries who can look after orphans and build schools. The problem usually isn’t a lack of able hands.

Voluntourism appeals to a fantasy of first worlders facing moral and existential ennui: that they will magically serve a useful purpose simply by being transplanted to a poorer country. People in those poorer countries are often more skilled and resourceful than the volunteers who show up to “help.” The primary good accomplished by these volunteers comes from the “tourism” part of voluntourism - transferring money to a poorer region of the world.

There are of course exceptions. If you have highly specialized skills that are in short supply - like engineering or medicine - you might actually be useful.

We often want to skip this step - to go directly to being filled with a sense of moral purpose, which, we assume, will motivate us to become skilled and effective people. In many cases it is the other way around - many possibilities for service are closed to us until we expand our capabilities.

Trapped by tropes and clichés

We have all inherited cultural narratives about what good people do. These narratives often rely on simplistic tropes. They have been polished down to be highly recognizable and easy to spot. Those who read a lot of rationalist blogs may recognize the Hitler/Gandhi contrast.

This is useful for thought experiments where you want big red glowing “GOOD” and “BAD” signs so that you can dispense with philosophical quibbles. It’s also useful for entertainment that isn’t too challenging.

When we set out to actually do good in the world, it is absolutely poisonous. It can cause us to fall into theatres of meaning that others have constructed to enrich and aggrandize themselves - such as the bulk of NGO, activist, and charity work.

Many years ago when I lived in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, I was approached by a woman who tried very insistently to get me to accept a sandwich out of the trunk of her car.

My guess is that she decided that she should feed the poor, and went to Canada’s poorest neighbourhood.

The sandwich itself looked like wonderbread, american cheese and probably margarine or mayo. From her appearance (fit, middle class), I doubt she ate that way at home. Highly processed calories are in no shortage in that neighborhood: I would frequently see Starbucks throwaways from drop-in centres dissolving in the gutters.

I am not trying to condemn her for clumsy efforts. Hopefully, she learned something from that experience and kept refining her efforts until she was able to do something more useful. A very simplistic moral trope - “it is good to feed the poor” - led her to something unproductive.

A form of this trap is looking for the “ideal victim” - the subject so completely undeserving of their misfortune that it is maximally virtuous to help them. Much of the pathology of the intersectional left fits this mold: looking for the ideal, legible subaltern such as the queer, trans, disabled colonized BIPOC.

Anyone who has spent much time around “the poor” knows they are not angels nor are they devoid of agency or responsibility. This doesn’t mean it is never virtuous to help them - it means operating on the ground requires more care and discernment than fiction or thought experiments prepare us for.

Cults

If you want to do good and don’t want to think too hard about it, there is a very good chance that you will find yourself trapped in some theatre of meaning created by others.

Usually, this theatre of meaning is created with the conscious or unconscious goal of the self aggrandizement and personal enrichment of its founders. It will direct your time, money and efforts to those goals. Whatever good they do will be an incidental spillover driven by a need for image cultivation.

This comes from our desire to offload the cognitive burden of thinking about the world to others. A good way of being on guard for such organizations and ideologies is to be aware of the “Ra egregore” - the temptation of poorly defined but noble sounding goals.

These are the sort of goals which haunt legacy NGOs in particular. Beware of any organization whose primary activities are activism, lobbying or “raising awareness.”

Beware also of any movement or organization whose goal is “saving the world” - grandiose goals are almost always a cover for narcissism - of both the group leader and group members.

A View that is Too Abstract and Global

We can sabotage ourself by trying to take too global a view of the situation. When we go too far beyond what we are capably of directly perceiving and acting upon, we insert mediating ideologies and organizations into our efforts.

We neglect the local for the global, but the global is precisely where our perspective is most likely to be distorted. The abstract and global is mediated by organizations, governments, experts, journalists and ideologies. People recycled dutifully for years (and still do) despite it being esssentially fake.

Effective Altruism and Fantasies of Economic Fungibility

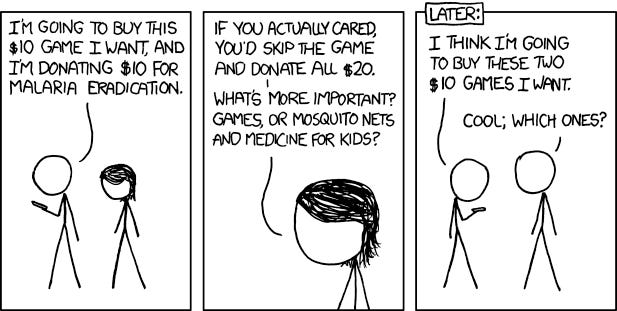

Effective altruism’s error does not occur at the core of the project - choosing actionable, measurable global health charities over “feel good” charities like the Children’s Wish Foundation - but rather occurs when useful heuristics are expanded beyond the zone where they are applicable.

Effective Altruism is looking for things that scale, and many important human endeavours don’t scale - like providing attentive, loving care for a child. It’s fine to look for things that scale, but looking only for good that scales neglects the most important aspects of the human condition.

Once something like bednets are identified as the most cost-effective life saving measure, there is a temptation of bednet maximization - everything not spent on bednets is basically murder. This is wrong of course. Bednets are the best intervention because they have not yet hit the frontier of diminishing returns. If we divert resources from everywhere else to maximize bednets, somewhere else becomes the new frontier of diminishing returns.

Money isn’t a good measure of resources because of some innate, platonic property, but because it is a fungible token of exchange for things people want - cathedrals, vacations, coffee, gasoline, etc. Money as a measure of resources that can be diverted to things like bednets only makes sense in a broader ecosystem of desire.

Thought experiments dreamed up by moral philosophy majors often take a mechanistic view of the world where clear, legible objectives must be traded off against each other. In most cases the practical world we live in is more ecological - we must keep different systems and drives in balance. “Which would you choose to keep, your heart or your lungs?” is not a meaningful choice - you will die without both. Hard tradeoffs are often tragic.

Consider the “lawyer in a soup kitchen” morality tale dreamed up by economists: it doesn’t make sense for a lawyer to volunteer in a soup kitchen, she should just lawyer more and send the money.

There is an element of truth to it, but it fails because it treats time mechanically - as fungible - rather than ecologically. The reality is that that lawyer has a limit to how much lawyering she is willing or able to do, and choosing to spend leisure time in a soup kitchen instead of watching Netflix is still a more pro-social alternative.

The antidote to this is to accept your role in a larger ecological system and trust that your immediate moral instincts towards those close at hand can be woven into a larger fabric. If they cannot, then the only moral world that can be built is fundamentally inhuman anyways.

This is not to suggest that it is *never* necessary to make morally counterintuitive choices in service of a greater good - but if you find yourself doing it often, something is wrong.1

Scalability

If you want to do things that scale, it often makes sense to start from the bottom up, rather than the top down. A company which promotes internally and maintains a “stockboy to CEO” pipeline has the benefit of management that understands the small frictions on the ground. The alternative is something like authoritarian high modernism - an imposition of “well meaning” systems that make people’s lives worse.

Another small example of top-down progress: Metro North, the railroad between New York City and its northern suburbs, renovated its trains, in a total overhaul. Trains look more modern, neater, have brighter colors, and even have such amenities as power plugs for your computer (that nobody uses). But on the edge, by the wall, there used to be a flat ledge where one can put the morning cup of coffee: it is hard to read a book while holding a coffee cup. The designer (who either doesn’t ride trains or rides trains but doesn’t drink coffee while reading), thinking it is an aesthetic improvement, made the ledge slightly tilted, so it is impossible to put the cup on it.

This explains the more severe problems of landscaping and architecture: architects today build to impress other architects, and we end up with strange—irreversible—structures that do not satisfy the well-being of their residents; it takes time and a lot of progressive tinkering for that. Or some specialist sitting in the ministry of urban planning who doesn’t live in the community will produce the equivalent of the tilted ledge—as an improvement, except at a much larger scale. Specialization, as I will keep insisting, comes with side effects, one of which is separating labor from the fruits of labor.

Nicholas Nassim Taleb, “Skin in the Game”

The best way to find scalable efforts to do good would be to look for some problem *you* suffer from that other people likely have as well - and find an elegant, simple way of solving it that can then be provided to others.

Conclusion - What Is To Be Done

Many (though not all) of the problems identified above boil down to not wanting to think. It’s fine to not want to think; cognition is not an unlimited resource. In not wanting to think, we rely on models of the world that inevitably fail to capture important aspects of reality - or outsource our thinking to bad actors.

This post has been about failures, rather than victories. I have perhaps fallen into the same trap as that posed by the silver rule: it is easier to identify problems than to offer positive, workable proposals.

However, I think there is a deeper underlying point, which is that there are abundant opportunities around us to do good, but we have to think about them. Many errors arise from wanting to defer our thinking to heuristics, systems or more confident personalities. To do good well may be in some cases to be invisible: no one will see the lives enriched or the suffering avoided. Good that is optimized for goodness and not legibility will often be like this; but that is the point. It is an end in itself, and we can only corrupt it by subordinating it to other ends.

An important exception of course is when your “moral” choices are not moral choices at all but are driven by self flattering egotism - the story you tell yourself about what a good person you are. See above.

Loved reading this. Also, a hug. 🫂 As David below said, you may be a bit hard on yourself. 😉

To respond to a bit of the last part you said, that lots of the problems arise because we do not want to think. I believe that is true, but maybe like half of it? I believe the other half is because we don't want to feel, like truly feel. If we ask ourselves, "Where does the need to help this person in front of me come from?" and really listen to our feelings, then I think the response following that will be much more powerful and truthful.

Anyway, good stuff, it feels like you really put an effort into it and I liked the examples you shared as well!

I appreciate the candor of your article. Perhaps you are a little hard on yourself.

What this article reminded me of was the definition of "empathy" and how its much more precise/surgical and less feely/impulsive than is often used in vernacular language. To truly put ourselves in another's position and understand their needs takes a lot of thought, rumination and information gathering. The first impulsive compulsion we have in a desire to ease someone's suffering may not actually be empathetic because we haven't taken the time to really understand their needs and situation. Very much like the sandwich lady.

I think one of the highest yield measures to then address local needs and improve the lives of those around us is be less distracted. With our mental attention and energies diverted towards social media, the news, the sports team, the TV show, the audiobook etc. we reduce our mental and emotional bandwidth to identify and meditate on opportunities to do good. When Elon bought twitter I thought the best and funniest thing he could do with it was to just delete it. So many people freed up from anxiously scrolling the timeline and perhaps then more able to direct their energies somewhere more positive. A fantasy for sure, but a nice one I think.